Concept of Applying Marked Surgical Bur for Impacted Third Molar Extraction: Case Report

ABSTRACT

Third molar extraction is a very common manipulation in dental practice, which involve risks of injury of the anatomical structures. Damage of inferior alveolar nerve during third molar removal can cause paresthesia of maxillofacial region in postoperative period. In order to prevent such kind of complications authors suggest using marked surgical burs.

KEYWORDS

Third molar extraction; Marked surgical bur

INTRODUCTION

Third molar extraction is associated with a risk of developing several intraoperative complications, including bleeding, trauma of soft tissues and adjacent teeth [1]. Iatrogenic injury of inferior alveolar nerve (IAN) poses the most severe danger which may lead to neurosensory deficits such as: anaesthesia, hyperaesthesia and dysaesthesia of the area supplied by the IAN during postoperative period [2]. Such complications can be caused by damage dealt to the content of the mandibular canal during fragmentation of the tooth. Currently, there is no solution that would allow performing controlled tooth sectioning. In order to provide a more predictable intervention and exclude nerve trauma during tooth fragmentation and osteotomy; the authors present a case describing removal of impacted mandibular third molar using marked surgical burs (Figure 1).

CASE REPORT

Patient K., 23 years old, complained of periodic pain in the right side of lower jaw.

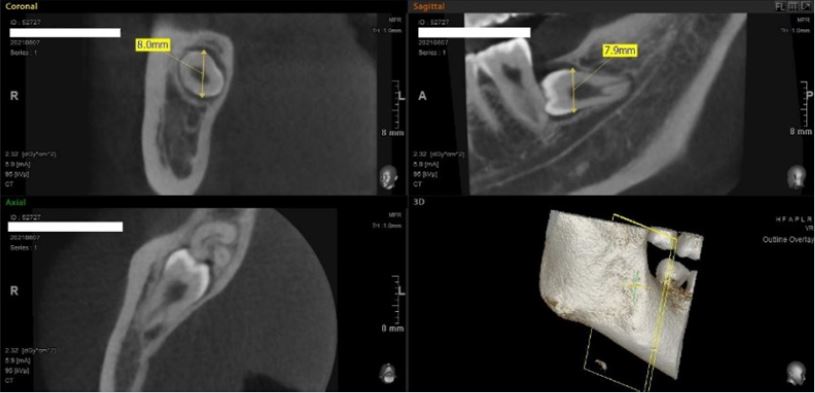

Treatment: After performing local anesthesia and reflection of the full thickness flap (Figure 2) the tooth was extracted with minimal traumatizing, crown part was removed using marked surgical bur immersed to a depth of 8 mm (Figure 3). The depth was measured using preliminary cone beam computed tomography (Figure 4). Controlled sectioning of the tooth made it possible to avoid excessive preparation of bone tissue and damage to anatomical structures of the mandibular canal (Figure 5). In this clinical case was used contra angle handpiece to prevent the formation of emphysema during tooth sectioning. The root was extracted (Figure 6), the wound was treated with chlorhexidine bigluconate solution 0,05%, sutures Polyamide 5-0 (Figure 7). The patient received recommendations. A second examination was carried out on the 7th day after the operation. The sutures were removed. The patient had no complaints. In the postoperative period, there were no signs of impaired sensitivity or paresthesia in the maxillofacial region.

DISCUSSION

Removal of the third molars is one of the most common procedures performed in the maxillofacial surgery. However, this procedure requires precise planning and surgical skills. There is always a risk of complications during surgical interventions. The frequency of complications after removal of the third molar ranges from 2.6% to 30.9% [3]. The spectrum of complications varies from minor expected consequences of postoperative pain and Edema to irreversible nerve damage, fractures of the mandible and lifethreatening infections. Minor complications are usually defined as complications that can recover without any further treatment. The main complications can be defined as complications that need further treatment and can lead to irreversible consequences [4]. Third molars can be asymptomatic, but they may also be responsible for significant pathology. Pain, pericoronitis, periodontal disease development on the second molar, resorption of the crown and/or root of the second molar, caries on the third or second molar and TMJ-symptoms are associated with the preservation of the third molars. More significant pathologies, such as infections of the fascial space, spontaneous fracture of the mandible, also odontogenic cysts or tumors may occur. There are numerous recent studies that identify risk factors for intraoperative and/or postoperative complications [5-8]. It is important for a dental surgeon to be familiar with all possible complications, which leads to early recognition and more effective elimination of the consequences of complications. Injury to the lingual or inferior alveolar nerves during the removal of the lower third molars is one of the most common causes of judicial processes in dentistry. The close anatomical connection between these nerves and the third molar puts them at risk of damage [9]. The frequency of these extremely rare complications varies from study to study and is difficult to pinpoint due to the small population studied. A fracture of the mandible during removal or in the postoperative period is a rare event but is a serious complication [10]. Decreased bone strength may be caused by physiological atrophy, osteoporosis, pathological processes, or may be secondary to surgical intervention. There is no reliable data on the frequency of fractures of the lower jaw, and risk factors have not been clearly studied. In the Arrigoni study & Lambrecht analysed 3,980 third molar removals. In this group, the complication rate was about 0.29%. The peak incidence occurs in patients over 25 years of age, whose average age is 40 years [11]. Intraoperative fractures may occur due to improper osteotomy and excessive pressure on the bone during tooth extraction. Most late fractures occur between two to four weeks after surgery during chewing.

More unusual complications include the spread of inflammatory processes to atypical areas of the brain and the cervical region. In one case, a subperiosteal orbital abscess occurred in a 35-year-old man after a single removal of the left lower third molar, which could have been caused by the spread of infection into the lower orbital fissure [12]. The other group is represented by subdural empyema and Hunt syndrome. In this case, a 21-year-old man had all four third molars removed. An abscess was found covering the right pterygoid-mandibular and sub masseteric spaces and extending to the infratemporal fossa. Although antibacterial therapy and drainage were initiated, he developed severe frontal headache and vomiting with a Glasgow coma score of 13 points. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a subdural cluster in the right temporoparietal junction. He underwent urgent cranial trepanation and subdural drainage [13].

Accidental displacement of the affected third molars, be it a fragment of the root, crown or the entire tooth, is not a common occurrence during extraction, but nevertheless is a well-known complication that is often mentioned in the literature [14]. However, there is only limited information about its prevalence and treatment. Displacement of the teeth or roots of the mandible usually occurs when it is located lingually, or when the lingual cortical plate is thinned and if the surgical technique is poor. The upper third molars may be displaced into the infratemporal fossa. Other unusual complications may include a violation of the patency of the respiratory tract were described by Moghadam & Caminiti A 32-year-old man experienced swelling of the soft palate due to postextraction hemorrhage after he underwent tooth extraction of the third molars in his dentist’s office. Computed tomography revealed a hematoma in the submandibular and lateral pharynx, which led to deviation of the oropharynx and narrowing of the airways at the level of the oropharynx. The patient was intubated for two days and treated with antibiotics and high-dose steroids [15]. Wasson et al. [16]., reported a case of severe hemorrhage during the removal of the affected third molar in a 60-year-old male patient. More than two litters of blood loss occurred before control was obtained using embolization of the facial and lower alveolar arteries [16]. In one report by Goshlasby et al. [17]. the development of right-sided retrobulbar hematoma after removal of the affected right third molar of the upper jaw was discussed. The resulting hematoma caused right periorbital Edema and ecchymosis with signs of proptosis. The maxillary incision was widened, the hematoma was drained, and the bleeding was controlled. It was believed that a branch of the posterior superior alveolar artery was damaged during extraction, and bleeding was traced into the orbit through the infraorbital fissure [17]. Sekine et.al., reports a case of extensive subcutaneous emphysema with bilateral pneumothorax during removal of the left lower third molar in a 45-year-old man. As in many cases of emphysema, a dental high-speed handpiece was used. Recognition of mediastinal emphysema after surgical removal is difficult due to the absence of absolute clinical symptoms and signs.

Thus, in practice, when removing the third molars, the surgeon may face many possible complications. Prevention of such complications is very extensive, starting with the correct preoperative diagnosis. X-ray examination helps to reduce the risk of complications during removal (source 3 about the importance of X-rays). Methods of X-ray examination include targeted X-ray, OPTG and computed tomography. A sighting of a tooth is a popular option for diagnosing most problems in the oral cavity. The method is based on the use of X–rays and a sensor receiver of these rays, which allows you to obtain data on the internal tissues of the tooth, as well as tissues surrounding the root. Given the size of the sensor, 1-3 teeth can be seen in one picture. It is mainly carried out to addition to the visual examination data, as well as quality of endodontic treatment. Also, the sighting image has a low X-ray load. It does not allow to assess the condition of the teeth in different planes, it is difficult to apply this method with limited mouth opening.

Computed tomography, which plays an important role in the diagnosis of retention of the third molars of both the upper and lower jaw. Computed tomography allows not only to assess the proximity of the roots of the third molars to important anatomical formations, but also to more clearly understand the anatomy of the roots of the teeth. Also, do not underestimate the level of equipment and tools used to remove the third molars. Rotary instruments should be sharp enough to ensure rapid osteotomy or fragmentation of root tissues. This clinical case demonstrates the use of marked surgical burs for controlled sectioning of horizontally located impacted third molar. The marking presented by the designers of the technology (Patent РФ 19 [Russian Federation] RU 11 206 854 U1) helps to perform accurate preparation of tooth tissues preventing damage of important anatomical structures and ensure safety of the operation and comfort of the patient as well as reduce duration of manipulation which is directly connected to the risk of postoperative infection [18]. The marking has the following division: 8, 10, and 12 mm which corresponds to the average width of third molar mandibular crowns [19]. The use of the marked surgical bur allows to perform sectioning within the whole width of the crown without risks of damage of anatomical structures. Depth of the bur planting can be defined in advance based on the results of cone beam computer tomography. Presently, in order to prevent injuring mandibular canal, Asana mi, Soichiro, Kasazaki suggest a technique involving sectioning of the crown not to the full width subsequent fracture using dental elevator [20]. It is assumed that the fracture will create a fracture line across the full width of the crown making it possible to remove it entirely. Clinical experience of the authors of the article shows that this technique is not controlled and is not effective due to absence of reference points. As a result, the crown part is fractured partially which may lead to complications (Figure 8).

CONCLUSION

The use of marked surgical bur in this clinical case made it possible to perform accurate sectioning of tooth tissues based on mathematically accurate preoperative planning and not on tactile sensations. Using of marked surgical bur applicable for removing of all types of impacted tooth. The markings on the bur allow the operator to control the depth of immersion, provide more control and reduce the time of the operation.

AKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors of the article would like to thank «STOMUS LLC» and especially Denis Pukhov. Also, authors express thanks to the member of the human rights council, scientist-historian and director Ponasenkov Evgeniy Nikolaevich.

REFERENCES

- Sayed N, Bakathir A, Pasha M, Al-Sudairy S (2019) Complications of third molar extraction a retrospective study from a tertiary healthcare centre in Oman. Sultan Qaboos University Med J 19(3): e230-e235.

- Leung YY, McGrath C, Cheung LK (2013) Trigeminal neurosensory deficit and patient reported outcome measures: The effect on quality-of-life. PLoS ONE 8(8): e72891.

- Jerjes W, El-Maaytah MD, Swinson B, Banu B, et al. (2006) Experience versus complication rate in third molar surgery. Head Face Med.

- Jin-Cheol K, Seong-Seok C, Soon-Joo W, Seong-Gon K (2006) Minor complications after mandibular third molar surgery: type, incidence and possible prevention. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 102(2): e4-e11.

- Yamada SI, Hasegawa T, Yoshimura N, Hakoyama Y, Nitta T, et al. (2022) Prevalence of and risk factors for postoperative complications after lower third molar extraction: A multicenter prospective observational study in Japan. Medicine (Baltimore) 101(32): e29989.

- Morrow AJ, Dodson TB, Gonzalez ML, Lang MS, Chuang SK (2018) Do postoperative antibiotics decrease the frequency of inflammatory complications following Third Molar Removal. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 76(4): 700-708.

- François Blondeau, Daniel NG (2007) Extraction of impacted mandibular third molars: postoperative complications and their risk factors. J Can Dent Assoc 73(4).

- Ya-Wei C, Lin-Yang C, Kuang-Sheng OL (2021) Revisit incidence of complications after impacted mandibular third molar extraction: A nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS One 16(2): e0246625.

- Ramadas Y, Sealey CM (2001) Third molar removal and nerve injury. NZ Dent J.

- Wagner KW, Otten JE, Schoen R, Schmelzeisen R (2005) Pathological mandibular fractures following third molar removal. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 34(7): 722-726.

- Arrigoni J, Lambrecht TJ (2004) Complications during and after third molar extraction. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed.

- Eltayeb AS, Karrar ML, Elbeshir EI (2019) Orbital subperiosteal abscess associated with mandibular wisdom tooth infection: A Case Report. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 18(1): 30-33.

- Ramchandani PL, Sabesan T, Peters WJN (2004) Subdural empyema and herpes zoster syndrome (Hunt syndrome) complicating removal of third molars. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 42(1): P55-57.

- Ozer N, Uçem F, Saruhanoğlu A, Yilmaz S, Tanyeri H (2013) Removal of a maxillary third molar displaced into pterygopalatine fossa via intraoral approach. Case Rep Dent 2013: 392148.

- Moghadam HG, Caminiti MF (2002) Life-threatening hemorrhage after extraction of third molars: case report and management protocol, J Can Dent Assoc 68(11): 670-674.

- Wasson M, Ghodke B, Dillon JK (2012) Exsanguinating hemorrhage following third molar extraction: report of a case and discussion of materials and methods in selective embolization. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 70(10): P2271-P2275.

- Goshtasby P, Miremadi R, Warwar R (2010) Retrobulbar hematoma after third molar extraction: case report and review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 68(2).

- Resnik RR, Misch C (2008) Prophylactic antibiotic regimens in oral implantology: rationale and protocol. Implant Dent 17(2): 142-150.

- Gayvoronskii IV, Petrova TB (2005) Anatomya zubov cheloveka.

- Soichiro A, Yasunori K Expert third molar extractions.

Article Type

Case Report

Publication history

Received Date: October 10, 2022

Published: December 07, 2022

Address for correspondence

Ivanova Elena Vladimirovna, department of oral surgery and implantology, Moscow Regional Research and Clinical Institute, Russia

Copyright

©2022 Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science, All rights reserved. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means as per the standard guidelines of fair use. Open Access Journal of Biomedical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

How to cite this article

Smirnov AD, Ivanova EV, Amhadova MA, Usaev TA. Concept of Applying Marked Surgical Bur for Impacted Third Molar Extraction: Case Report. 2022- 4(6) OAJBS.ID.000526.